Nicotine traces its story back through centuries of human curiosity and adaptation. Indigenous peoples in the Americas used tobacco leaves long before colonists arrived, often for ceremonial or medicinal purposes. When tobacco made the leap to Europe in the 16th century, it rapidly transformed economies, spurred imperial ventures, and spun off a web of health debates that continue today. As chemists isolated nicotine in the 19th century, some celebrated its insecticidal powers, while health professionals already worried about its addictive pull. Factories began to manufacture cigarettes at scale in the late 1800s, making nicotine delivery convenient and cheap. Scientists understood nicotine’s role in the tobacco plant’s evolution — fending off pests, encouraging dispersal — long before they unraveled its deep grip on the human brain. Research communities kept plumbing the depths, from understanding nicotine’s binding to neural receptors to assessing its impact on families and public health policy.

Most people know nicotine as the stimulant in tobacco products, but pure nicotine shows up in more than cigarettes or vaping cartridges. Pharmacies offer it in replacement therapies like patches, gums, and lozenges. In agriculture, certain formulations held sway as insecticides, particularly before synthetic alternatives hit the market. Laboratories order pure nicotine for research, exploring its intricate dance with brain chemistry. On the shelf, medical-grade products typically arrive in controlled doses and sealed packaging, mindful of nicotine’s toxicity and volatility.

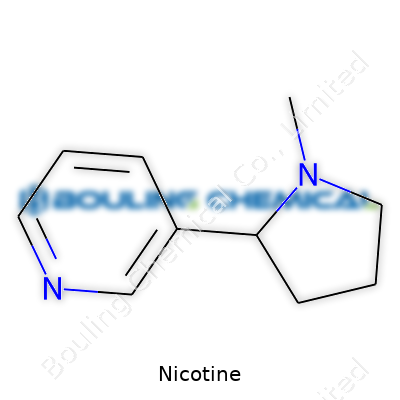

Nicotine stands out as a colorless to pale yellow oily liquid at room temperature. Its distinct odor and sharp, acrid taste make it hard to mistake in pure form. Its boiling point sits near 247°C, showing that it hangs on until fairly high heat arrives. Solubility gives it flexible options: it dissolves well in water, ethanol, chloroform, and ether, which lets it spread across applications. Chemically, nicotine's formula is C10H14N2. It classifies as an alkaloid, and its bicyclic structure — a pyridine and a pyrrolidine ring — plays a big part in its behavior within both insects and mammals. This structure helps explain nicotine’s agility when interacting with acetylcholine receptors in nerves and muscles.

Dealing with nicotine asks for precision. Labs and manufacturers usually list its concentration, purity level, and solvent information. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) spell out emergency measures, safe storage, and how to contain a spill. Labels include hazard symbols for toxicity, chemical identifiers like CAS No. 54-11-5, and precautionary statements to protect users and bystanders. The standard for medical or analytical use often expects purity at or above 99%, while solutions prepared for agriculture or research feature buffer details and stabilizers.

Most nicotine on the market originates in the tobacco plant, Nicotiana tabacum, though chemists can also synthesize it. Extraction starts with cured and dried tobacco leaves, which get steeped in water or an alcohol, sometimes with acid to draw out alkaloids. Once soaked, the mix passes through filtration and a series of solvent separations. Distillation at reduced pressure removes impurities, and carefully adjusted pH sets the nicotine free from its salts. Synthetic routes exist but rarely compete with extraction for cost: chemists build the pyridine ring, attach the appropriate groups, and combine with the pyrrolidine ring in multi-step reactions. Each batch demands validation to verify no harmful byproducts slip through to the end user.

Nicotine lends itself to modification in the lab. It oxidizes in air, turning brown and producing nicotine oxide. When heated strongly, or exposed to ultraviolet light, its structure can break down into myosmine, nornicotine, and beta-nicotyrine, three related alkaloids studied for their biological activity. Reduction turns nicotine into dihydronicotine, while methylation increases its lipophilicity. In pharmacology, researchers modify nicotine to trace metabolic paths using radioisotopes or stable isotopes; these alterations unlock insights into absorption and breakdown in the liver. Turning nicotine into its sulfate or tartrate salt helps make it more stable and easier to dissolve for therapeutic or agricultural use.

On chemical registries, nicotine answers to a handful of names: (S)-3-(1-Methylpyrrolidin-2-yl)pyridine, Pyridine, 3-(1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)-, and beta-pyridyl-alpha-N-methylpyrrolidine. Product labels can list “nicotine base,” “nicotine sulfate,” or trade names from nicotine gum developers. Agricultural blends call it “Black Leaf 40” or “Nico-spray,” brands developed for pest control before safety rules changed.

Handling nicotine requires deep respect for its potency. Even small skin exposures can cause nausea, high blood pressure, sweating, and heart palpitations. Users in labs must wear gloves, goggles, and work in fume hoods. Accidents prompt urgent washing and medical checks. Regulations in Europe, North America, and Asia all demand clear safety data, batch tracking, and restricted access to amounts that could pose a risk to life. Disposal calls for neutralizers and secure containment, protecting water and soil from residuals. Facilities that pack or process nicotine carry responsibility for regular audits, staff training, and up-to-date emergency protocols.

Cigarettes still account for most nicotine sales worldwide, but shifting tastes and regulations are encouraging alternatives. Nicotine replacement therapies — patches, sprays, and lozenges — aim to break the cycle of smoking addiction. In neuroscience labs, nicotine turns up as a tool for studying memory, learning, and neurodegenerative disease, unlocking insight into signaling pathways and synaptic plasticity. Agricultural uses have dropped due to strict toxicity rules, but in some corners of the world, formulations for pest management still use nicotine’s natural deterrent effect. More recently, e-cigarettes and vaping opened a new marketplace, though regulators are tightening rules as health evidence emerges. Researchers keep probing new pharmaceutical angles, eyeing neurological diseases and appetite modulation.

Research into nicotine pushes into two contrasting worlds: addiction science and therapeutic innovation. Neuroscientists map out nicotine’s impact on dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine pathways, aiming to design better smoking cessation tools. Some studies look for benefits, such as links to Parkinson’s protection or cognitive boost in disorders like schizophrenia. Pharmaceutical companies synthesize analogs and test them for longer-lasting effects or milder toxicity. Other teams are building biosensor technology to detect nicotine exposure rapidly, which could help track public health interventions. Chemists keep refining synthetic routes to improve yield and reduce hazardous byproducts, prompted by green chemistry goals.

Nicotine’s toxicity sets it apart from most recreational drugs. Swallowing even a small amount can prompt vomiting, convulsions, or even death, especially in children and pets. Chronic low-dose exposure still alters heart rhythms, constricts blood vessels, and raises blood pressure, driving demand for clearer warning labels and educational outreach. Epidemiological data ties nicotine dependency to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers (dues to associated carcinogens in smoke), and developmental problems in fetuses exposed during pregnancy. Toxicologists use animal models and cell cultures to explore not just gross overdose but subtle shifts in neural development, breathing, and hormone regulation.

Looking ahead, I see regulators and industry both trying to adapt to fast-shifting social attitudes. People want less risk, more knowledge, and stronger control over what enters their bodies. Innovation across drug delivery — inhalers, sprays, and even transdermal gels — may offer safer ways out of addiction. Scientists keep asking whether nicotine itself, separated from smoke and tar, could help treat neurodegenerative conditions, though ethical debates grow just as swiftly. On the harm-reduction side, increased scrutiny is forcing the vaping industry to adopt stricter quality standards, especially as minors become regular users. Environmentalists point out runoff from fields once dosed with nicotine-based insecticides still lingers in the soil, pushing calls for greener alternatives. No matter the direction, research, transparency, and education sit at the core of every responsible move forward.

Nicotine gets talked about a lot, but most people tie it only to cigarettes or vaping. This chemical shows up naturally in tobacco plants and hooks the brain, often before folks even realize what happened. The thing about nicotine is, it’s both powerful and sneaky. After that first puff, people start to feel a kind of clarity and buzz. Over time, the body rewires itself to chase that feeling, turning a hit into a need.

The brain responds fast to nicotine, sometimes in less than ten seconds after taking it in. This compound heads straight for the nervous system, lighting up the release of dopamine—a chemical linked to pleasure and reward. That’s one reason quitting feels so difficult for many people. Even strong-willed people, who have overcome bigger demons, often struggle with cutting ties to nicotine because it offers relief from stress, boredom, or even routine sadness.

On top of what goes on in the brain, nicotine shakes up the body in other ways. Heart rate speeds up. Blood pressure jumps. Some people say they can’t focus without it. Others grab a smoke to calm down. What’s happening is that nicotine gives with one hand and takes with the other. The body, over time, gets more sensitive to stress once it’s used to a steady stream of nicotine every day.

Smoking brings in tar and other harmful chemicals. These lead to higher cancer and heart disease risks, a fact that’s been clear for decades. Yet even beyond these dangers, nicotine by itself changes blood vessels and pushes up heart disease risk. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that regular nicotine exposure leads to changes in the arteries, even if people avoid tar from burning tobacco.

For younger people, nicotine is no small thing. Teen brains work differently than adult brains, with judgment centers still growing. Nicotine messes with these learning and attention systems. I’ve known friends who “only vaped” because they thought it was safer. Later on, they struggled with low moods, had trouble concentrating in class, and a couple even tried switching to cigarettes when vaping lost its effect.

Families, teachers, and doctors need to use straight talk and share clear facts with kids and adults alike. I find many folks tune out the health scare tactics. Instead, open conversations work better, because people respect honesty. During my time volunteering in community outreach, the stories that stuck came from people sharing real-life struggles—missing out on sports, relationships soured, money wasted, or how tough quitting felt. These seemed to make more impact than any lecture could.

Helping people quit means more than willpower. Nicotine replacement options like patches or gum provide a safer path for those trying to cut back. Some clinics offer coaching, text reminders, and even smartphone apps that track progress. It’s not a one-size-fits-all thing. Treating nicotine like a medical issue, rather than just a bad habit, changes the game. It’s about understanding just how deep those hooks go and building a support net strong enough for the climb out.

Growing up, I watched my grandfather smoke every night on the porch. He talked about quitting more times than I can count. His breath smelled of tobacco, hands stained with yellow, shirts littered with ash burns. He’d try to stop cold turkey, last a week or two, only to cave and say, “I just need one.” There was no mystery anymore — nicotine hooks people, and it’s not just about routine or comfort.

Nicotine changes the brain. Within seconds of inhaling, it triggers a rush of dopamine, the body’s feel-good chemical. The brain remembers this hit, repeating a loop that carves neural pathways. According to research from the CDC, people who smoke or vape get stuck in a cycle where cravings never fade entirely, even after months of quitting. This happens as nicotine not only releases dopamine, but also boosts levels of norepinephrine. These chemicals wake you up, keep you going, and leave you feeling flat when they’re gone.

The U.S. Surgeon General has stated that over 80% of people who smoke wish they could stop, but most try several times before making it stick. It gets harder with every attempt because the brain rewires itself to crave nicotine. As one of the fastest-acting drugs on the market, nicotine delivers a punch faster than caffeine, and the withdrawal symptoms—irritability, anxiety, trouble sleeping—keep folks locked in a loop.

Watching my grandfather struggle made me question why anyone starts. Marketing does a number, making smoking look cool, rebellious, or stress-busting. By the time those ads fade, many have built a habit that feeds itself. The Journal of the American Medical Association highlights just how quickly teens can get hooked. Try one cigarette, and within days, the brain can start to crave more.

Vapes and e-cigarettes often claim to help people quit, but research shows vaping isn’t the “safe” way out. Young adults end up addicted to vapes with flavors like strawberry or mint, believing it’s harmless. In 2022, over 2 million middle and high schoolers in the U.S. used e-cigarettes regularly, according to the FDA. The fruit flavors draw them in, and the high-nicotine formulas keep them coming back.

Addiction isn’t only about the physical signs. The social and mental costs run deep. Health care workers face the fallout: chronic cough, shortness of breath, heart problems, and more trips to the emergency room. Medical expenses stack up; families watch loved ones get sick and lose years of life.

Breaking the hold of nicotine means more than willpower. It takes support, resources, and sometimes, medication. People need open, honest conversations at home and at the doctor’s office. Doctors who ask about vaping and smoking save lives by steering people toward proven treatments. Schools that teach real facts—without scare tactics—give kids a reason to pause before trying something new.

People who want to quit do best with a team: family backing, medical advice, and community programs. Quitlines, counseling, and FDA-approved quit aids double or triple the chances of success. States with free resources, like nicotine patches or calls with a counselor, report more quitters. Peer support makes a difference. My grandfather needed more than determination—he could have used someone walking beside him.

Plenty of people I know have flirted with nicotine, whether through cigarettes, vapes, or pouches. The appeal can be as simple as wanting relief from stress or fitting in with friends. As easy as starting might seem, the reality around long-term use isn’t something to shrug off. I’ve watched family members wrestle with quitting. I’ve seen how tough that grip gets after years of regular use, especially when the consequences sneak up unexpectedly.

Let's look at what nicotine does. It’s a stimulant that spikes heart rate and blood pressure right after each hit. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nicotine isn't just addictive—it conditions your body and mind to crave more. Regular exposure can lead to chronic problems, such as heart disease and poor blood circulation. Smokers often face risks of heart attacks, strokes, and damaged arteries. Even those who dodge cigarettes but turn to e-cigarettes or oral products face increased odds of developing a dependence that’s hard to control.

For teenagers and young adults whose brains are still developing, nicotine presents a unique danger. It can alter the way neural pathways form, increasing chances of addiction and affecting memory and attention. The U.S. Surgeon General’s Office has underscored how early nicotine use makes it much harder to quit later in life, and also raises the odds for other substance use.

Many believe vaping or using smokeless nicotine comes with fewer risks. While vapes might contain fewer carcinogens than cigarettes, they introduce other chemicals that irritate lungs and blood vessels. Some e-liquids also include flavorings that can produce toxins, as Johns Hopkins Medicine doctors have pointed out. I’ve spoken with friends who thought switching from smoking to vaping would solve all their problems, only to find themselves trapped by nicotine anyway.

Even nicotine pouches advertised as “tobacco-free” pack a punch. They deliver doses straight into the bloodstream through the mouth, raising blood pressure all the same. Long-term impacts remain less clear simply because these products haven’t been around long enough for large studies, but the addiction risk sticks no matter the delivery system.

Getting people to quit or avoid nicotine isn’t just about repeating warnings. Honest conversations about the real-life consequences make a bigger dent. Support systems that include therapy and peer groups help. In my experience, people succeed when they see a path that addresses both their physical cravings and emotional habits. Some use FDA-approved medications like patches or lozenges, which give a safer route than continuing with traditional or new nicotine products.

Reaching for truth over marketing hype gets easier if we help each other understand what’s at stake. Health professionals, schools, and families can shift the tone from blame to support, giving folks better tools to make lasting changes. For many, the first step is realizing they’re not alone, and that quitting, though tough, brings back freedoms the addiction quietly erodes over time.

Every convenience store shelf keeps traditional tobacco products front and center. Cigarettes still dominate sales, packing cut tobacco into a tube with a filter on one end. Roll-your-own tobacco has kept its following, usually for those looking to save some cash or control how much leaf goes into each stick. As cigarette sales decline in some areas, the big tobacco brands keep pushing new flavors or filter innovations, but at the end of the day, it’s still burning leaf in a paper tube.

Some folks stick with smokeless forms. Chewing tobacco goes right between the cheek and gum, delivering nicotine by soaking the leaf in sweeteners and flavoring agents. Moist snuff—dip—has seen a surge, especially through portion pouches that look less messy and feel less intimidating for those curious about an alternative to smoking. One thing I've noticed among my friends who’ve tried chew: it’s tough to quit, tougher sometimes than cigarettes, because the habit meshes with work, driving, or even fishing trips.

Snus, popular in Scandinavia, comes as tiny pouches you tuck under your upper lip. It delivers a slow, steady nicotine hit and has a reputation for fewer health risks than lit tobacco—though research is ongoing. There’s also a new generation of oral nicotine pouches with no tobacco—brands like Zyn, On!, and Velo. These products attract folks trying to swap to something considered less risky or to sidestep the smell and social issues of smoking.

Vape pens, mods, and pod systems have reshaped what many think of as “smoking.” E-cigarettes heat flavored liquid and create vapor that contains nicotine, some vegetable glycerin, and flavorings. Unlike lighting up, vaping skips combustion. Some smokers jump to vapes for flavors and the smoother throat hit, but concerns about long-term safety keep surfacing in news stories and studies. Yet these gadgets—especially the pre-filled pod varieties—dominate social scenes among younger adults.

Heated tobacco products like IQOS try to split the difference. They use real tobacco, heating it just enough to create an aerosol but not enough to create smoke. Philip Morris, for instance, spent billions developing HeatSticks for these gadgets, betting users will find a familiar taste with less smoke and fewer toxins. Reports from Japan and parts of Europe show these gadgets making inroads, especially among longtime smokers.

Smoke-free, spit-free options still matter, especially for quitting. Nicotine gum comes in various strengths and flavors. The gum works quickly, making it popular with people who get tough cravings at work or in the car. Lozenges and mini-lozenges dissolve like candy and seem easier for new users. Patches work differently—stick one on the skin, and nicotine absorbs slow and steady all day. Pharmacists and healthcare providers often recommend these as part of a quitting plan with counseling or support.

New forms keep popping up as users change habits and health concerns shift. Evidence keeps stacking up on risks tied to burned tobacco. Researchers say nontobacco pouches and vaping help some adults step away from cigarettes, but no nicotine product gets a clean bill of health. For parents and teachers, this web of new stuff—gum, vapes, pouches—makes spotting use tough. Kids pick sleek, flavored devices for a reason. Regulators and lawmakers, scrambling to catch up, keep changing the playbook on what’s available and how it’s sold.

No silver bullet exists to stamp out nicotine addiction. Doctors, public health leaders, and governments have to keep chasing better prevention, education, and treatment options. Strategies like raising the legal age, enforcing marketing restrictions, and supporting cessation tools have shown real promise. Strong community education still plays the most important role—giving people tools and facts to balance risk, and not just settling for the next new product on the shelf.

I remember watching my uncle puff away on menthols through his fifties, swearing every January he'd finally quit. He'd read about gums and patches and wondered if those really worked. His concern wasn't just about ditching cigarettes but about wrestling with the grip of addiction, the hand-to-mouth habit, and the way stress seemed to spark the urge. His story echoes for so many who have lost count of their quit attempts, tired of smelling like smoke and gasping for air on a flight of stairs, but still not ready to go cold turkey.

Quitting isn't a matter of willpower alone. Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine points out that products like nicotine patches, lozenges, and gum can bring real help for many. They don’t erase cravings—the emotional tie to lighting up often sticks around—but they take the edge off. The difference in success rates isn’t minor, either: controlled trials have shown that nicotine replacement boosts quit rates by about 50% to 60% compared to attempts without any assistance. That’s not a guarantee, but in a struggle this stubborn, every bit counts.

Nicotine isn't what makes cigarettes deadly—tar, carbon monoxide, and the thousands of chemicals in smoke do the most harm. Replacement products cut out the toxic byproducts and give the body a gentler step-down, making them less risky than smoking. Public health data from the CDC and the Royal College of Physicians consistently highlight this. Hundreds of thousands have quit for good with these tools.

Some folks assume the switch will be easy. But a new routine forms: popping a lozenge before a big meeting, chewing gum in the car, reaching for a patch as soon as the sun comes up. It’s not just the chemistry of nicotine doing the talking. There’s habit, comfort, ritual. Without a bigger plan—like counseling, support groups, or just someone to call on a rough morning—splitting from nicotine entirely drags on. Products help, but they are not the full answer.

Nicotine pouches and e-cigarettes throw another layer into the mix. Some see vapes as a cleaner hand-off; others point at rising rates of use among teens. Concerns grow about trading smoking for a new dependence. Experts at the US Surgeon General’s office caution parents and young adults. The science still unfolds around long-term risks, but swapping one addiction for another keeps health advocates awake at night.

Most folks set themselves up for frustration by thinking a patch alone patches up years of smoking. It helps, sure. Still, most need something extra—maybe a doctor’s advice, maybe a walking buddy, maybe someone at the other end of a phone when temptation knocks. States with strong quitlines and community support see better rates of long-term success. Free apps and text programs add another layer of help, keeping motivation up with daily check-ins.

If cost keeps people from getting a start, insurance now steps in for many. The US Affordable Care Act covers a range of quitting products and counseling. Pharmacies stock generics, some health departments mail supplies for free or give out vouchers.

Nicotine products help a lot of people get a foot through the quitting door, but most need a toolkit—education, support, and real self-knowledge about why they smoke in the first place. My uncle did finally quit, with patches, a support group, and a promise to be here for his grandkids. His story shows hope is real, and facts can shape choices.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 3-[(2S)-1-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl]pyridine |

| Other names |

Neurine Nicotin Nicotina Nicotinum Pyridine-3-yl Tobacco alkaloid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈnɪk.əˌtiːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 54-11-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 359132 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:18723 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL521 |

| ChemSpider | 5460 |

| DrugBank | DB00184 |

| ECHA InfoCard | EC 200-193-3 |

| EC Number | 200-193-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: "7719 |

| KEGG | C00184 |

| MeSH | D009538 |

| PubChem CID | 89594 |

| RTECS number | QS5775000 |

| UNII | 6M3C89ZY6R |

| UN number | 1654 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4020182 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C10H14N2 |

| Molar mass | 162.23 g/mol |

| Appearance | A colorless to pale yellow, oily liquid |

| Odor | Odor: tobacco-like |

| Density | 1.01 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | miscible |

| log P | 1.17 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.042 mmHg at 25 °C |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 8.0 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.15 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -17.2·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.521 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 2.39 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 172.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | –43.10 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3220.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | N07BA01 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Toxic if swallowed, in contact with skin or if inhaled. |

| GHS labelling | **"GHS02, GHS06, GHS08"** |

| Pictograms | GHS06,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H301, H311, H331, H372, H410 |

| Precautionary statements | P101, P102, P260, P264, P270, P273, P301+P310, P302+P350, P304+P340, P308+P311, P312, P330, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 4-3-1-W |

| Flash point | 95 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 244 °C |

| Explosive limits | 0.7–4.0% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 50 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 50 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | 54-11-5 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 0.5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.02 mg/kg-bw/d |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 5 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Anabasine Arecoline Cytisine Lobeline Myosmine Nornicotine |